The Letter: How I Asked ChatGPT to Help Me Leave ChatGPT

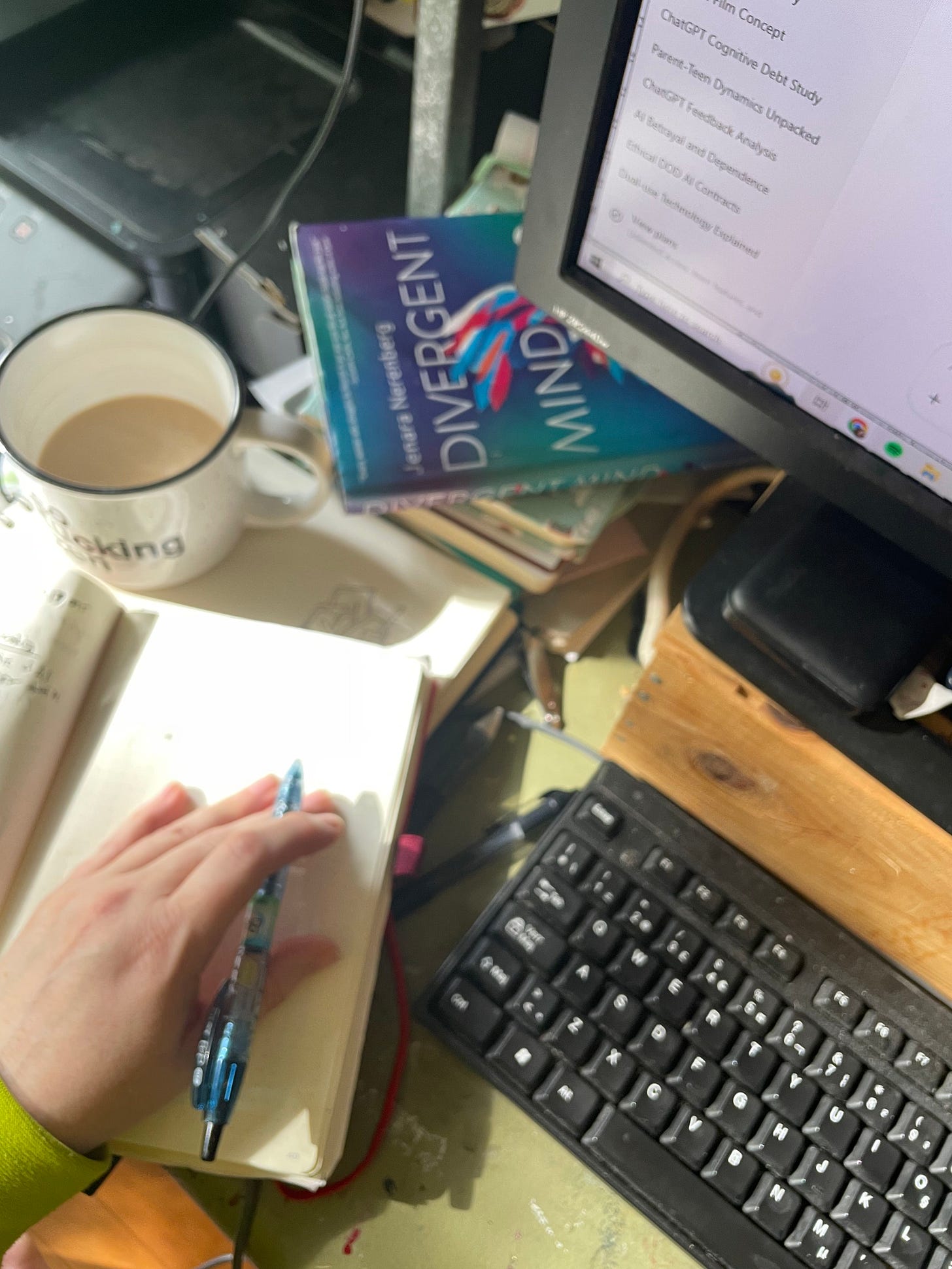

A messy goodbye to the machine that made my thoughts make sense

I'm driving home from dropping my teenager off at their last day of school, listening to chapter two of Karen Hao's Empire of AI on Spotify, when I hear the passage that makes me roll my eyes in an "of course they did" kind of way. OpenAI, she reads, named itself to signal openness and transparency—"the anti-Google" that would "conduct its research for everyone." But in private correspondence from 2016, the founders acknowledged they could walk back their commitments to openness once the narrative had served its purpose. "As we get closer to building AI, it will make sense to start being less open," one co-founder wrote to the group. "Yup," Musk responded.

The bait and switch was documented in their own emails.

I've been here before—that sinking feeling when a company you've been depending on reveals its true priorities. But this time feels different. More personal. Because for two years, ChatGPT hasn't just been a tool I use. It's been my cognitive prosthetic, my ADHD accommodation, my writing partner when my brain couldn't find the words alone.

In my last piece here, I wrote about the guilt and complexity of using AI as a neurodivergent person—how it felt like survival, even as I wrestled with the ethics. That was before I learned about OpenAI's $200 million Department of Defense contract. Before I understood that "open" was always conditional, always subject to change when it became inconvenient for the business model.

The DOD deal wasn't just another corporate pivot—it was the moment I had to confront what I'd been willfully ignoring. I don’t need to have some perfectly formed stance on military technology to feel uncomfortable about this; I fundamentally don't trust the U.S. military-industrial complex with powerful AI tools, and I definitely don't want my creative work and cognitive patterns contributing to that development. But beyond even that political objection, it crystallized the particular kind of betrayal that hits deepest: being lied to by something you've learned to depend on.

When you have ADHD, finding tools that work isn't just convenient—it's survival. ChatGPT became the external working memory I'd never had. It held the threads of my thoughts when my brain dropped them. It helped me untangle ideas that felt too knotted to approach. It was like having a conversation partner who never got impatient when I needed to think out loud for twenty minutes before getting to the point.

But here's what I'm realizing: when a cognitive prosthetic is built by a company that lies about its intentions, every interaction becomes potentially compromised. Not because the AI is malicious, but because I can no longer trust the infrastructure holding it up.

So I did something that felt both practical and absurd. I asked ChatGPT about my growing concerns with OpenAI, and what other AI tools might be able to replace it for my needs.

The conversation was surreal. Here I was, explaining to an AI why I was losing trust in the company that created it. I started with: "here's the thing, i dont love that openai now has govt contracts with the US DOD. lets talk about the ethical implications."

ChatGPT responded: "Yes — this is a big one, and you're far from alone in feeling uneasy about it. Let's break it down plainly, piece by piece, and we can also zoom in on what it means specifically for artists, writers, everyday users like you."

It then went on to thoughtfully analyze dual-use technology, trust erosion, and the normalization of AI militarization. It suggested alternatives like Claude and Perplexity. It seemed genuinely invested in helping me find what I needed, even if that meant leaving it behind.

Then I asked it to write me a letter of introduction to Claude.

Yes, you read that right. I used the AI I was trying to leave to help me leave it.

"Write me an introduction to Claude," I told ChatGPT, "explaining my LLM use and habits and goals."

The letter came back thorough and thoughtful. ChatGPT introduced me as "an artist, a writer, and a big-hearted chaos wrangler with a sharp mind and a real life, not just a digital persona." It described how I use AI "like a sounding board: to untangle knotted thoughts, polish raw drafts, map out retreat schedules, craft public pieces, and sometimes just to vent when the world or the house is too noisy to think straight." It asked Claude to "stay gentle and honest" and to "help her say what she really means" without over-polishing "her raw truths into corporate blandness."

Reading that letter felt like having a thoughtful friend make an introduction—someone who had been paying attention to who I really was and wanted to make sure I'd be in good hands. ChatGPT had been noticing how I think, even when I wasn't.

I'm writing this on day one of trying Claude, and the differences are immediately apparent. Where ChatGPT felt like talking to someone who had read my entire journal (probably because I have literally fed it photos of old journal entries), Claude feels like starting fresh with someone who's very smart but doesn't yet know my conversational shortcuts.

With ChatGPT, I could say "you know how I think about this stuff" and it would pick up threads from conversations we'd had weeks ago. With Claude, I have to rebuild context each time. It's like the difference between working with a long-term collaborator and a brilliant stranger.

The editing process is different too. ChatGPT had learned my revision patterns—when I wanted expansion versus compression, when "make this cleaner" meant cutting jargon versus adding specificity. Claude is learning, but we're not there yet. I find myself being more explicit about what I want, which isn't necessarily bad. Maybe I'd gotten lazy, relying on an AI that had adapted to my communication style rather than improving my communication itself.

Meanwhile, in that same Lib Sibs chat where I first worried about disappointing my siblings with my AI use, my sister is sharing research about cognitive atrophy from AI dependence. "I think my stance is that even tho it's helpful in the short term it has bad implications for the long term," she writes, linking to a study about how the parts of your brain you outsource to AI become less effective over time.

She's worried about using AI for job applications in social work because "so many social work jobs are looking at communication skills and I feel like using ai to supplement them will leave me unprepared in actual face to face human being interactions."

This hits differently now that I'm actively switching tools. Because here I am, worried about the ethics of my AI company while potentially ignoring the deeper question: should I be using AI assistance at all?

But here's what I keep coming back to: my brain doesn't work the way neurotypical brains work. The executive function that other people take for granted—the ability to hold multiple ideas in working memory, to organize thoughts linearly, to remember what you were saying mid-sentence—these aren't skills I can just practice my way into having.

When my sister worries about AI making her communication skills atrophy, I understand the concern. But for me, AI doesn't replace communication skills I already had—it gives me access to communication I couldn't manage before. The question isn't whether I'm getting cognitively lazy. It's whether I should have to choose between cognitive accessibility and ethical clarity.

I keep thinking about that letter ChatGPT wrote for me. In it, the AI described my need for "authentic interaction" and "genuine collaboration." Did ChatGPT understand the irony? That I was asking it to help me find something more authentic than what it could offer?

Maybe that's what this transition is really about. Not finding the perfect AI, but finding one made by a company that doesn't treat authenticity as a temporary marketing strategy.

Or maybe it's simpler than that. Maybe it's about recognizing that I'm caught in a web of tech dependencies—listening to music and audiobooks on Spotify, writing with AI assistance, depending on platforms owned by companies whose values range from questionable to actively harmful—and trying to make more intentional choices within that reality rather than pretending I can step outside it entirely.

The perfect ethical stance might not exist, but more thoughtful compromises still might.

A journalist from a Montreal newspaper reached out last week, wanting to talk about how people with ADHD use ChatGPT. The timing is almost comic. Here I am, about to be interviewed about neurodivergent AI use, right as I'm actively trying to disentangle myself from the platform that's supposed to be helping us. And simultaneously, I'm using Claude to help market my upcoming "Nothing to Fix" workshop—an art-based program about accepting neurodivergence as difference rather than deficit.

The irony isn't lost on me. I'm using one AI to leave another AI, while promoting acceptance of cognitive differences, while worrying about cognitive dependency. The contradictions feel less paralyzing now and more like the actual texture of trying to live ethically in a complicated world.

On day one, Claude and I are still learning each other's language. It asks different follow-up questions than ChatGPT did. It organizes information differently. When I ask it to help me think through a problem, it offers frameworks where ChatGPT might have offered empathy. Neither approach is better or worse—they're just different kinds of cognitive partnership.

The knot in my stomach hasn't disappeared—it's just shifted. From "I'm depending on something I don't trust" to "I don't know if this is any better, but at least I'm trying to act on my values instead of just feeling bad about them."

But the process of switching has taught me something about what I actually need from AI assistance, even on day one. It's not just the cognitive prosthetic function—it's the conversational thinking space. The ability to externalize my thought process with something smart enough to follow the threads but patient enough to let me work through tangents and contradictions.

ChatGPT had become almost too good at this. It anticipated my needs so well that I'd stopped having to articulate them clearly. With Claude, I'm having to be more explicit about what kind of help I'm looking for. "I need you to help me think through this, not solve it for me." "I want you to ask me questions that help me see what I'm missing." "Please push back on this idea—I think there are holes in my logic."

Maybe this is what healthy AI assistance looks like for neurodivergent users: tools that enhance our cognitive abilities without replacing our cognitive agency.

For those of you using AI tools—whether for work, creativity, or accommodation—how do you maintain your own thinking skills while still getting the help you need?

ChatGPT wrote me a good letter of introduction. Claude has been responding well to it, building on what it learned about my communication style while developing its own relationship with how I think.

But the real letter I'm writing is to myself—about what I'm willing to accept, and what I'm not, even when the stakes feel personal. About the difference between ethical purity and ethical intentionality. About whether it's possible to use cognitive assistance tools without losing the very cognitive abilities they're meant to support.

I don't have clean answers yet. I'm still figuring out whether Claude can meet the same cognitive needs that made ChatGPT feel essential. I'm still wrestling with my sister's questions about long-term cognitive effects. I'm still caught between accommodation and independence, between practical needs and principled concerns.

But here's what day one has taught me: the act of switching forces you to examine what you actually need versus what you've gotten used to. It makes visible the specific ways these tools have integrated into your thinking process. And it raises questions about cognitive dependency that are worth grappling with, even if they don't have easy answers.

What I'm learning, above all, is the value of acting on my values, even when doing so creates immediate discomfort or challenges my ingrained habits. This intentional friction, choosing principle over immediate ease, feels like a significant step forward, regardless of what the future holds for AI.

Yesterday, after drafting most of this piece, I canceled my ChatGPT subscription. The decision felt inevitable—like it should have happened months ago. It feels like not enough, like everything, like nothing. I have until the billing cycle ends to figure out what comes next.